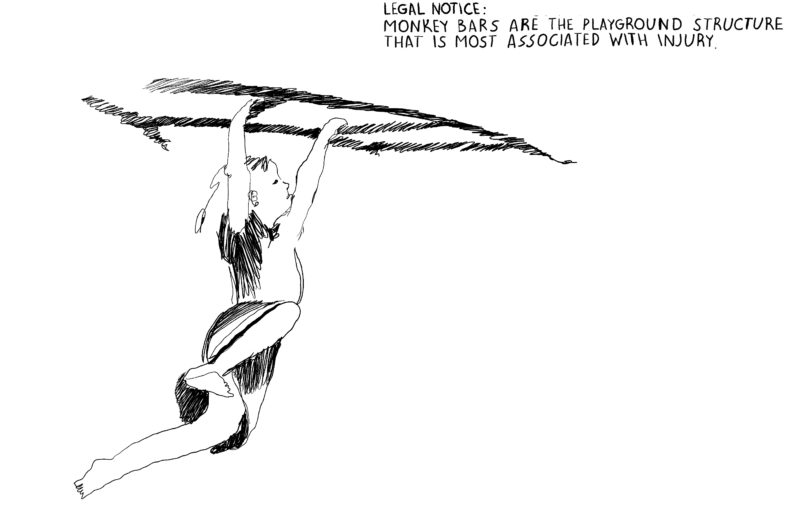

I always go back to the Girl on the Monkey Bars. I sketch scenes from the slow-motion film that runs before my eyes: torso swaying, hands desperately holding on, body weight shifting, muscles flexing, failing, succeeding. Her palms are sweaty. Irritated skin turns pink and then tomato-red. The Girl is in a state of perpetual discomfort of swinging legs and twisted elbows. The doctors (1; 2) warned her: monkey bars are the playground structure heavily associated with injury. Nonetheless, she persists.

1. Setting off.

This piece is written in solidarity with the Monkey Bars and the Girl holding one another. Each paragraph, each thought is a moment of simultaneously gripping on and slipping off. Each movement in the narrative is a disjointed and clumsy attempt to propel a piece somewhere (perhaps not towards an end, but towards an opening?), in a way that has a critical intention in mind, yet is saturated with multiple pulls, in the way limbs and muscles jerk in search of momentum. The essay is an experiments-in-the-making (for which I beg your forgiveness and invite responses of all kinds, but no hate mail please!) where I mix sketches with short vignettes and sprinkle on theoretical promiscuity.

“Sweaty concepts”, writes Sara Ahmed (2017), come slowly, come out of bodies in discomfort, of pushing against the world in a desire to transform it. This piece of writing is also a partial view into my sweating with the concept of play in early childhood education. How might we chip away at the universal image of a child at play? How might we warp the notion of “play” from a naturalized shape of public marvel (at playing children) to a distorted struggle that resonates against the public institutions of “good” teaching and parenting? What might become possible in early childhood education if we take up play not as yet another dress rehearsal of already existing social norms, but as propositions of constructing worlds (good, bad, ugly, and different), powers, knowledges?

I now wish to make space on these pages for Sara Ahmed’s writing in a page-long excerpt from Living a Feminist Life because, firstly, the sustained space this quote takes in this essay echoes her very propositions of continued, strenuous working at something that matters. It is also a question of uncovering the circumstances and others (bodies and minds) that shatter or replenish my/your own experience and thinking. Lastly, I hope that you trace Ahmed’s writing as she does it: along your own skin, bearing all the weight of your situatedness.

I write this piece as I work, alongside educators and children, in a playground space in a city in Canada’s ‘chemical valley’. It’s a stifling 340C by 9 am. The soft strap of the plastic face shield that I, like the educators, am wearing over the face mask captures the drops of sweat that want to get into my eyes. We collect rocks and sticks. We take off shoes, squeezing clay soil and the fuzz of the picnic blanket between our toes. Dust glues to damp skin. On Monday afternoon, the unescapable heat mixes also with the air horn alarms. It’s the refineries’ weekly emergency system testing in case of a chemical leak. If you saw our bodies strained, sweating, sticking, slowing, would you name us playing?

By trying to describe something that is difficult, that resists being fully comprehended in the present, we generate what I call “sweaty concepts.” I first used this expression when I was trying to describe to students the kind of intellectual labor evident in Audre Lorde’s work. <…> Her words gave me the courage to make my own experience into a resource, my experiences as a brown woman, lesbian, daughter; as a writer, to build theory from description of where I was in the world, to build theory from description of not being accommodated by a world. A lifeline: it can be a fragile rope, worn and tattered from the harshness of weather, but it is enough, just enough, to bear your weight, to pull you out, to help you survive a shattering experience.

A sweaty concept: another way of being pulled out from a shattering experience. By using sweaty concepts for descriptive work, I am trying to say at least two things. First, I was suggesting that too often conceptual work is understood as distinct from describing a situation: and I am thinking here of a situation as something that comes to demand a response. A situation can refer to a combination of circumstances of a given moment but also to a critical, problematic, or striking set of circumstances. <…> Concepts tend to be identified as what scholars somehow come up with, often through contemplation and withdrawal, rather like an apple that hits you on the head, sparking revelation from a position of exteriority. <…> Concepts are at work in how we work, whatever it is that we do. We need to work out, sometimes, what these concepts are (what we are thinking when we are doing, or what doing is thinking) because concepts can be murky as background assumptions. But that working out is precisely not bringing a concept in from the outside (or from above): concepts are in the worlds we are in. By using the idea of sweaty concepts, I am also trying to show how descriptive work is conceptual work. A concept is worldly, but it is also a reorientation to a world, a way of turning things around, a different slant on the same thing. More specifically, a sweaty concept is one that comes out of a description of a body that is not at home in the world. By this I mean description as angle or point of view: a description of how it feels not to be at home in the world, or a description of the world from the point of view of not being at home in it. Sweat is bodily; we might sweat more during more strenuous and muscular activity. A sweaty concept might come out of a bodily experience that is trying. The task is to stay with the difficulty, to keep exploring and exposing this difficulty. We might need not to eliminate the effort or labor from the writing.

Not eliminating the effort or labor becomes an academic aim because we have been taught to tidy our texts, not to reveal the struggle we have in getting somewhere. Sweaty concepts are also generated by the practical experience of coming up against a world, or the practical experience of trying to transform a world.

<…> We should be asking ourselves the same sorts of questions when we write our texts, when we put things together, as we do in living our lives. How to dismantle the world that is built to accommodate only some bodies? (Ahmed, 2017, pp. 12-14)

1__2. Everyone is naked

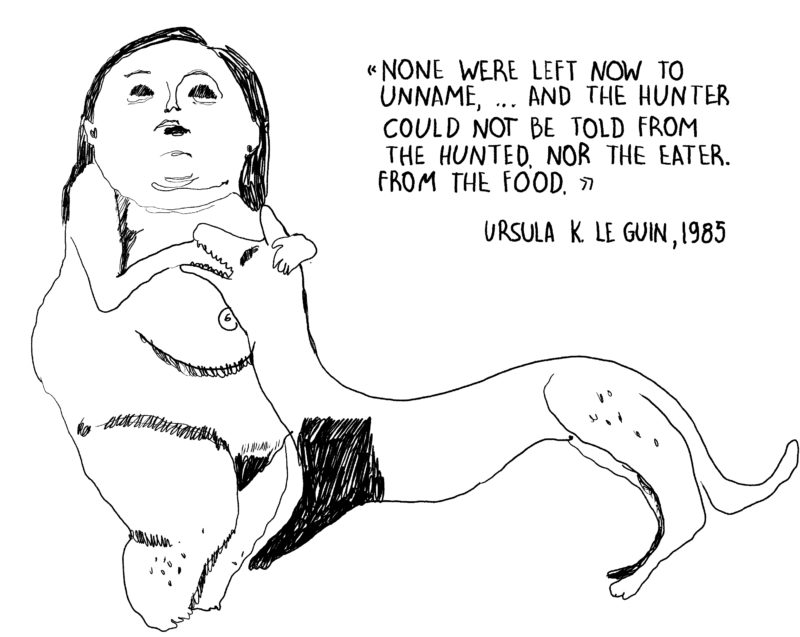

In just a few paragraphs, Ursula K. Le Guin (1985) sets the stage for a feminist uprising:

They used to be called

yaks, rats, poodles, sea otters,

and other names which are now lost.

She is a woman formerly known as Eve.

Like them, she takes on namelessness

in a refusal of certainty of knowing and being known.

She and they crawl and swim

and lay closely to one another.

They and she touch,

eat and become eaten,

they taste blood and affect, in which fear and love

are no longer distinguishable from one another.

Play, we are often told, is difficult to define but is easy to recognize. This magic trick fools you only if you buy into the homogeneous images of shiny happy children playing. As if they were speaking about play, fellow admirers of Le Guin’s short story “She Unnames Them” (which inspired the above passage), Gough and Adsit-Morris write (2020, p. 218): “Naming is not just a matter of labeling existing distinctions. Assigning a name constructs the illusion that what is named is genuinely distinguishable from all else”.

2. (Un)naming

What does (un)naming ask of us? Not to fall silent, refusing words that make up our sometimes-shared vocabulary. Not to reprise the move of a vengeful god who takes away the common language to stop mere humans from reaching heaven. Not to look up alternatives in a thesaurus (although tracing word origins, definitions and synonyms is infinitely fascinating). In thinking of language and power as inexplicably linked, we ought to consider naming + un-naming + not-naming as a feminist practice of thinking critically how, and at whom, violence is directed through words (Ahmed, 2017); to fiercely question constructions that purport to explain away but themselves ought to be explained (Pignarre & Stengers, 2011, p.13):

What might need (un)naming in early childhood education? What is “free play” free of? What are “loose parts” loose from?[1] What does “risky play” actually risk? Who is excluded from the mantra of “the right to play” (Article 31, UN Convention on the Rights of a Child) that adorns nearly every article and document concerned with play in the Global North? How might we move beyond sweeping generalizations that couple play and children’s so-called nature (as in “natural response”[2], or “natural curiosity and exuberance”[3])? How do we un-mechanize the X-marks-the-spot on the playground where an educator takes her supervisory stand?

2_3. They are here.

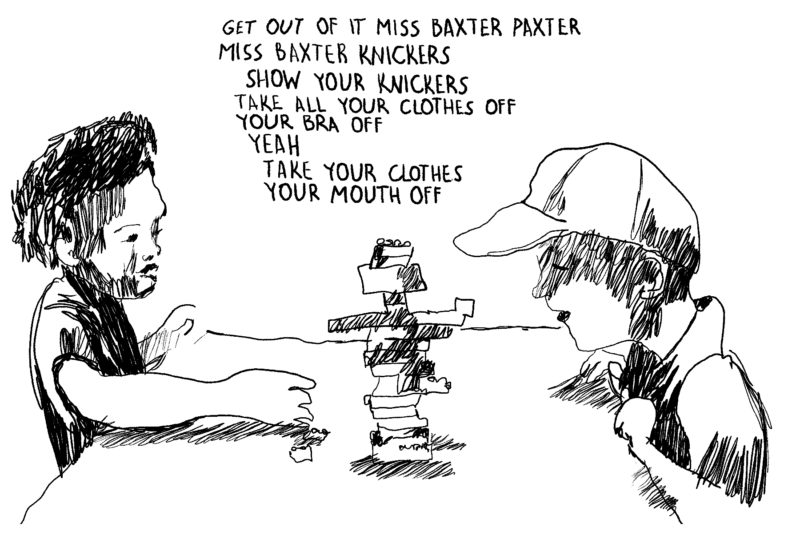

The opening vignette of Valerie Walkerdine’s Schoolgirl Fictions (1990) acts out for the reader moments of play in a nursery school that tightly weave gender and power discourses with Lego bricks. This play is volatile, spilling from the boundaries of classroom appropriateness into sexualized violence:

What I wish to gesture towards with the introduction of this very small piece of Walkerdine’s writing is the need for more complex thinking (and, consequently, more complex language, conversations, practices, documentations, ideas, etc, etc) about play in ECE settings. Neither the binary categories of safe/risky, free/guided, nature/playground, outdoor/indoor, toys/loose parts, etc nor the non-critical adjectives like fun, voluntary, adventurous, constructive, etc are capable of grasping the complexity (and the darkness) of play, thus impoverishing its pedagogical and world-making possibilities.

Moreover, failing to critically consider the taken-for-granted language of play may leave our educational practice impotent. Consider, for instance, the closed circuit of the “romanticized amnesia” (Malone, 2015, p. 6) of risky and nature play movement (see the works of Mariana Brussoni and Richard Louv). Here, we are told, the playing child’s development and well-being are under threat by lack of access to nature, parental fears (aha, the mothers are to blame!) or societal emphasis on safety standards that “smother” adventure (Vollmar & Lindner, 2018). While safety standards may dictate certain conditions for work and play, they are neither pedagogically instructive nor indestructible. The work done by, for example, members of the Common Worlds Research Collective shows what play(ing) is possible when we refuse to be swallowed by bloated regulatory jurisdictions (whether safety or developmental), and instead work to agitate bonds that wish to capture the playing human.

Not only do I suggest that safety standards cannot constraint the pedagogical potentials of the work of educators and children in outdoor and playground settings, but that the destitute landscapes surrounding many childcare sites across Canada can be, must be, sites to think education politically. Plastic play structures, tarmac steaming in the summer heat, dirt and wood chips, chain-link fences, weeping mulberries and cedar hedges, shade sails, trike loops, and sand boxes are the very conditions that make us ask how did we come to think of a trike as a staple of early-year centers’ playgrounds? What do we enact when we insist that sand must stay in the sandbox? How might we care for the dandelions that spoil our lawns? What stories might we tell when we see the chain-link fence as keeping in, andkeeping out, and letting through, and springing back, and framing, and breaking, and, and, and…

3. Play and learn

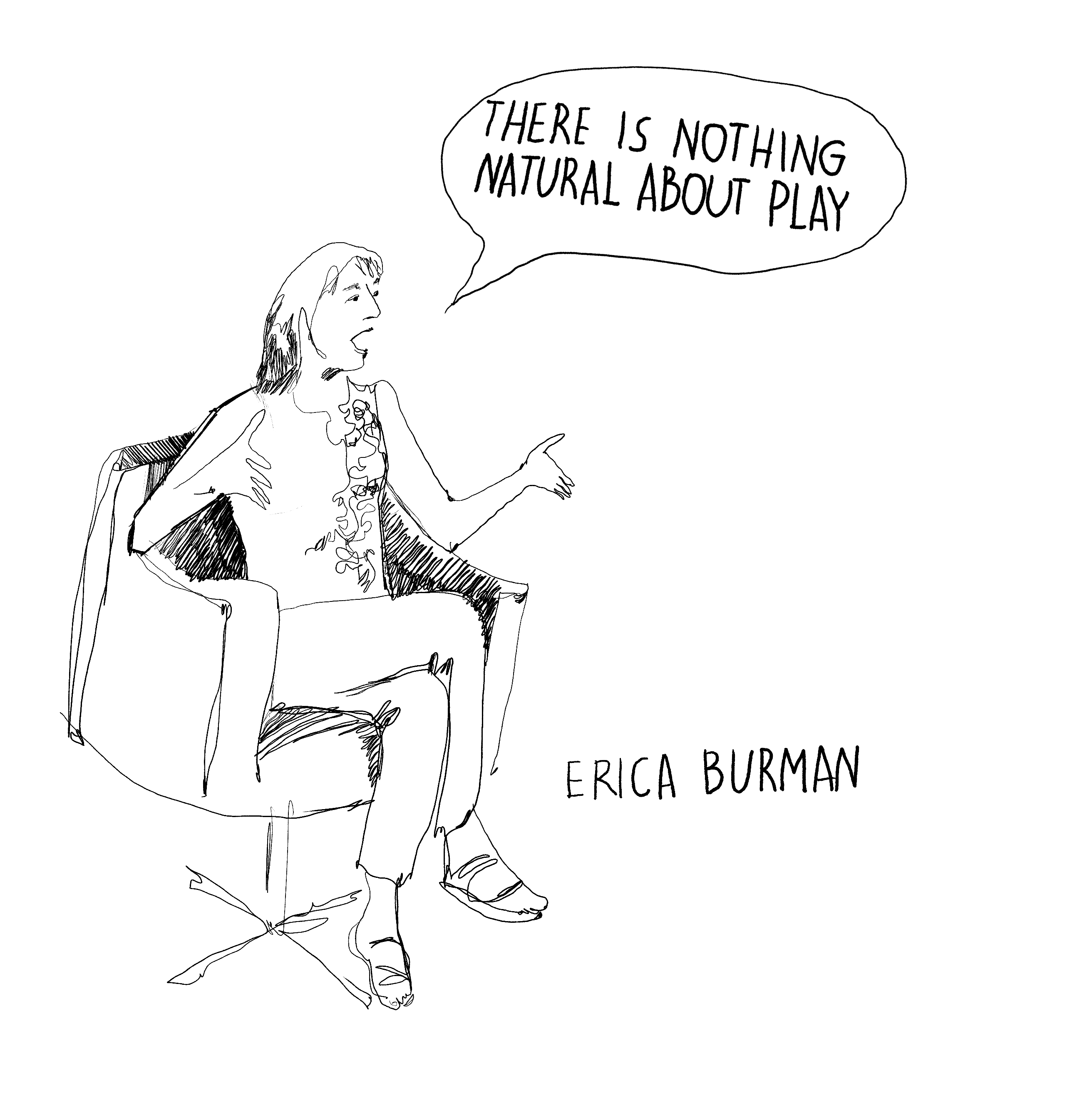

I favor the boldness of Erica Burman (2017) declaring: “there is nothing natural about play” (p. 254). By attending to how play is constructed in ways that reflect class privileges, neoliberal values, culture, Western rights-based world views, and regulation (of mothers and teachers, in particular), we, too can follow Burman in tracing how neither play itself, nor our management of it are benign or free.

If we take pedagogical processes as subject-forming, then play-based learning[4] is, too, an ethical practice open to “ontological violence” (Todd, 2001, p. 435). This means that not only educators organizing “free play” (when distinguished from “guided play”, as in Danniels & Pyle, 2018, referenced in the CECE document above) is an oxymoron, but any suggestion that this play is indeed “child-directed, voluntary, internally motivated, and pleasurable” (p. 1) ignores entirely the political instruments that wish it into existence and the ethical questions such practice ought to raise. Thus, play-based learning techniques both delineate and produce the very activity they claim innate to children. They also are offered as a solution to a problem (learning improved through play) before asking a critical question: what and whom is it for?

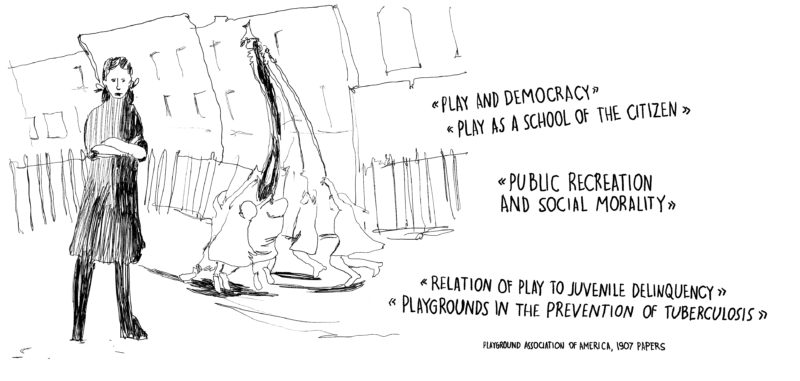

3_4. In business

Within developmental discourses, play is paradoxically narrated as both children’s natural inclination and as their work. Declarations like “unstructured play is the business of childhood” (Canadian Public Health Association) echo the Progressive reformers’ ambition to “fix” juvenile delinquents by teaching them how to play (the right way) on newly-organized playgrounds (Hines, 2017; McArhur, 1975) and trope of the era commemorated in Maria Montessori’s utterance: “play is the work of the child” (in Mobily, 2018, p. 152).

4. Letting go

Reflecting critically on the offering of ‘risky play’ (normally defined as thrilling outdoor play with a possible occurrence of physical injury; see Sandseter & Kennair, 2011) easily reveals the end-product: resilience building, itself the nation state’s favourite trait in a neoliberal citizen committed to self-care. Within a broader context, the regime of resilience obscures suffering and marketizes endurance of Black and Indigenous people, women and children, and marginalized others (see Casco-Solís, 2019; Clay, 2019; Burman, 2017; Lindroth & Sinevaara-Niskanen, 2017). Within the discourses of play, we might ask to what (un)known dangers or crisis does risky play plan to govern children towards? How might play (particularly in outdoor settings, where much of the ‘risky play’ conversations are situated) be considered as more than means of developing harder (resilient), better, faster, stronger children?

Sweaty play as a pedagogical project asks us to undo play as the last defense line in the project of an innocent child and that of a developing child. Accepted narrations of play as “free” or materials as simply constituting loose bits and bobs that are used “dependent on the children’s interests and imagination” (Dietze & Kashin, 2019, p. 83) blossom from the same child-centeredness that houses developmentalism and anthropocentrism (Land, et al., 2020). They ask us to either marvel at the beautiful play, or to subvert it, narrowly defined, in supporting determinacy of existing regimes and neoliberal futures. In defiance, we might think of play as experiences which conjure up something “that makes us new, that makes us into something that is neither one nor two, that brings us into the open where purpose and functions are given a rest” (Haraway, p. 2008, p. 237). So conceived, play requires a recognition of interdependence beyond a child, of releasing the tight grip and letting the body feel the pull of the next bar, putting the Girl’s world on the line.

Footnotes

[1]

In asking this question, I repeat Cristina Delgado Vintimilla who blew up my world by uttering it in February 2020 at Responding to Ecological Challenges with/in Contemporary Childhoods: An Interdisciplinary Colloquium on Climate Pedagogies.

[2]

Council of Ministers of Education of Canada, 2012. Online: https://www.cmec.ca/Publications/Lists/Publications/Attachments/282/play-based-learning_statement_EN.pdf

[3]

How Does Leaning Happen?, 2014. Online: https://files.ontario.ca/edu-how-does-learning-happen-en-2021-03-23.pdf

One thought on “Sweet Sweaty Play”

Comments are closed.