Magazine

Editors’ Note – Studying: An Invitation to Early Childhood Education

Editors’ Note – Studying: An Invitation to Early Childhood Education

Editorial Issue 5, Issue 5, Magazine, Uncategorized

September 2023

College Professors: Actors¹ in Early Childhood Education

College Professors: Actors¹ in Early Childhood Education

Issue 5, Magazine, Pedagogist Discussions Issue 5, Uncategorized

September 2023

Thinking with Waste

Thinking with Waste

Issue 5, Magazine, Pedagogist Discussions Issue 5, Uncategorized

September 2023

Dialogues on Complexifying Care in ECE

Dialogues on Complexifying Care in ECE

Issue 5, Magazine, Pedagogist Discussions Issue 5, Uncategorized

September 2023

Thinking with Study in Early Childhood

Thinking with Study in Early Childhood

Essay Issue 5, Issue 5, Magazine, Uncategorized

September 2023

In Conversation with Dr. Adam Davies

In Conversation with Dr. Adam Davies

Essays Issue 4, Issue 4, Magazine, Uncategorized

October 2022

Returning as/with Post-Secondary Pedagogists

Returning as/with Post-Secondary Pedagogists

Issue 4, Magazine, Pedagogist Discussions Issue 4, Uncategorized

October 2022

On Inaugurating and Sustaining the Work of a Post Secondary Institution Pedagogist: Collectivity, In-Betweens, and Having a ‘Why’ – an interview with Bo Sun Kim

On Inaugurating and Sustaining the Work of a Post Secondary Institution Pedagogist: Collectivity, In-Betweens, and Having a ‘Why’ – an interview with Bo Sun Kim

Magazine, Pedagogists Discussions Issue 3, Uncategorized

June 2021

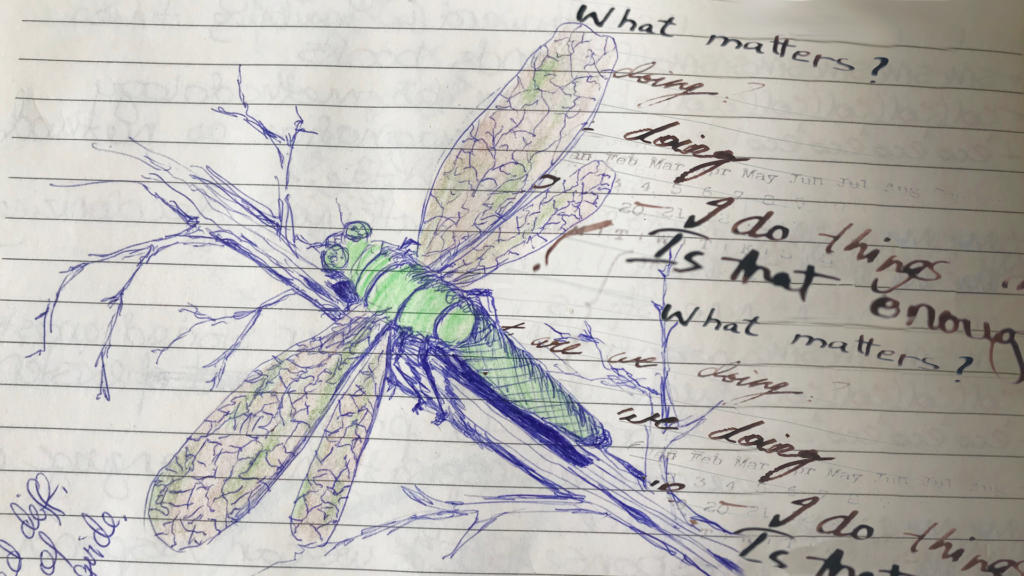

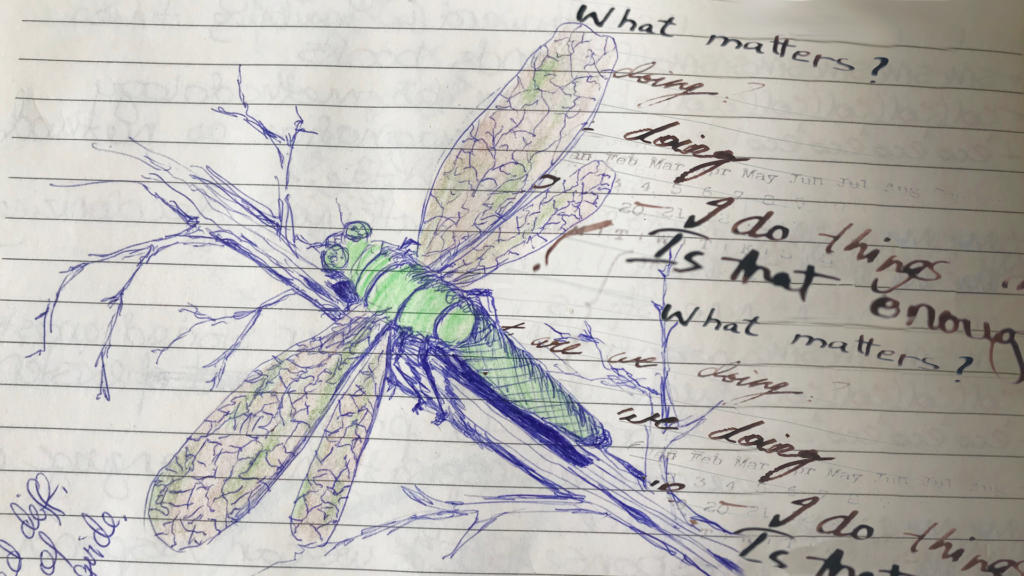

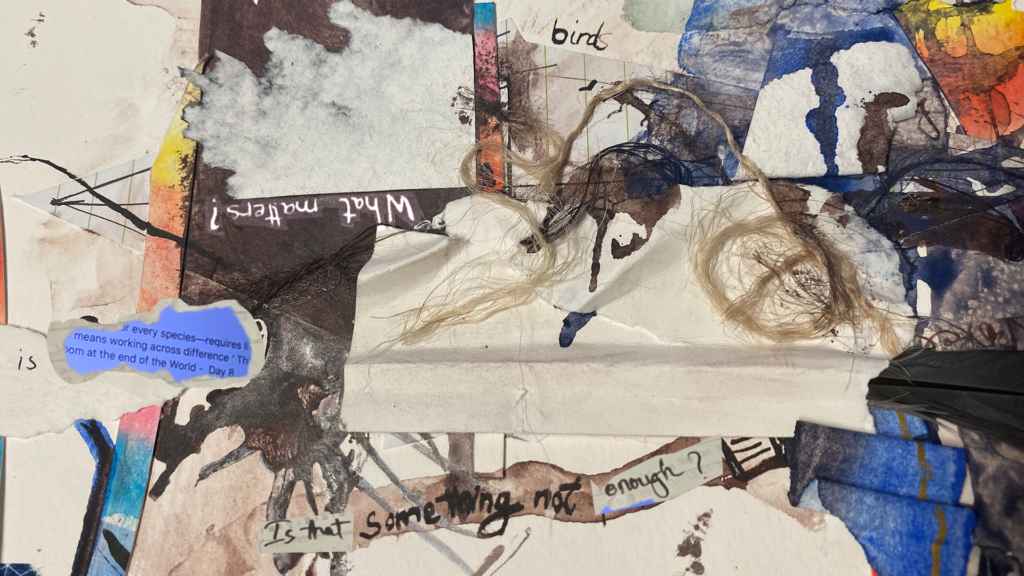

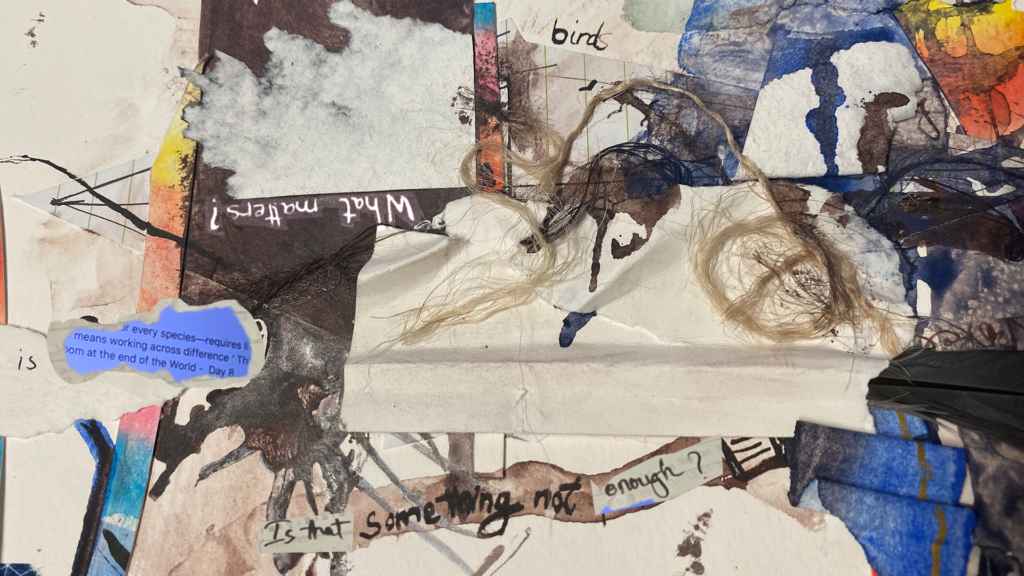

Journaling as a Choreographic Practice

Journaling as a Choreographic Practice

Magazine, Pedagogists Discussions Issue 3, Uncategorized

June 2021

Recollecting Practices of Attending and Creating Exposures: Conversations, Estrangements, Movements, Affected Intentions, and Risks

Recollecting Practices of Attending and Creating Exposures: Conversations, Estrangements, Movements, Affected Intentions, and Risks

Essay Issue 3, Magazine, Uncategorized

June 2021

Sweating the Fact(s) of my Body (+Mermaids) as a Pedagogist

Sweating the Fact(s) of my Body (+Mermaids) as a Pedagogist

Essays Issue 2, Magazine, Uncategorized

March 2021

On Becoming a Pedagogist: Brief Thoughts on Pedagogical Documentation

On Becoming a Pedagogist: Brief Thoughts on Pedagogical Documentation

Essays Issue 2, Magazine, Uncategorized

March 2021

Decolonizing Place in Early Childhood Education

Decolonizing Place in Early Childhood Education

Essays Issue 2, Magazine, Uncategorized

March 2021

On Becoming a Post Secondary Pedagogist: Working with Students, Faculty, and Institutional Realities

On Becoming a Post Secondary Pedagogist: Working with Students, Faculty, and Institutional Realities

Magazine, Pedagogist Discussions Issue 2, Uncategorized

March 2021

On Early Childhood Education Encountering Pedagogy: An Interview with Veronica Pacini-Ketchabaw

On Early Childhood Education Encountering Pedagogy: An Interview with Veronica Pacini-Ketchabaw

Interviews Issue 1, Magazine

December 2020

What Would be Possible if Education Subtracts Itself from Developmentalism

What Would be Possible if Education Subtracts Itself from Developmentalism

Essays Issue 1, Magazine

December 2020