Exposures were introduced to us within the pedagogical project of becoming pedagogists through The Pedagogist Network of Ontario (PNO; formerly the Centre of Excellence for Early Years and Child Care) and the British Columbia Early Childhood Pedagogy Network (ECPN). Within these projects, although exposures might have seemed new to us, they were not a practice without a vibrant biography. Exposures emerged through the history of Cristina Delgado Vintimilla’s work as the pedagogista of the Centre for Excellence, and exposures were created as a concept in an earlier course taught by Cristina, the Role of the Pedagogista, at Capilano University[1]. We were invited by Nicole Land, Cristina Delgado Vintimilla, Veronica Pacini-Ketchabaw, Randa Khattar, Fikile Nxumalo, and Kathleen Kummen to write an essay to re-enliven our experiences of past exposures. We were asked to think about exposures creatively and pedagogically by drawing on the connections that we noticed between the exposures that we participated in.

As a group of past regional coordinators and research assistants who participated in projects that enact the role of a pedagogist in the colonial nation state of Canada, we situate ourselves in work that puts dominant practices in education into tension. We have seen how taken-for-granted practices seek to simplify, and to make educational processes less complex and more oriented toward implementation. As participants in these projects, we worked to amplify complexities towards envisioning contextual pedagogical processes that respond to our specific places and times. Specifically, as regional coordinators we worked alongside pedagogists to craft pedagogical projects that were grounded in their own and our shared pedagogical intentions, and that traced the histories and presents of particular organizations and places. When we began our roles as regional coordinators, many of us encountered the practice of exposures for the first time; we now sense our way backwards and forward through these memories of beginning to practice exposures.

When we use the term exposure, we attend to the living history of this practice as instantiated through Cristina’s thinking and pedagogical experimentation. In this essay we meet exposures and explore some of the ways we try to think with their practice. We think this practice through vignettes and imperfect remembering. We are attending here to the invitation of the practice of exposures as described by Cristina on the PNO website:

“Estrangement, refiguring, altering, being called by a sensing that can’t yet be made sense of are the generative instantiations that exposures offer to pedagogists, and that in turn pedagogists offer to their milieu.”

For this essay, we have come together again as current pedagogists and past regional coordinators to write about some of the exposures we attended and that we have (now) organized through a mixture of prospective and retrospective narratives. This collective retracing and recollecting of our experiences with exposures lead us to write this essay in a series of vignettes. For us, these vignettes are not narratives that add context to a point that we are trying to make. They are instead how we actively remember and how we move through these memories to make meaning of how we have come to know exposures. The way these vignettes read might at first seem strange. In a different way, we were surprised that this was the first time that we had collectively paused to revisit the exposures. In this essay, we try to move through some exposures in particular ways. One of these ways is through language. Each vignette has a form of beginning and we think that in reading, you will also meet us at a beginning where we were still holding onto an instrumental language that could not yet speak to the complexities of exposures. We first tried to evoke some of the naive movements of entering different vocabularies and experiences. Each vignette, then, in some ways sits with the discomfort and uncertainty of becoming as we move through those beginnings towards the questions and propositions that we now want to think with. We begin with the awkwardness of not knowing and trying to meet a pedagogical experience even when we might have entered through more naive starting points such as preparation, necessity, frustration, anxiety, and busyness.

In relation to the time that has passed since the exposures took place, our recollections of these exposures convey the exchanges, moments, and encounters of these events in imperfect fragments. Thus, early in our discussions we moved away from revisiting exposures as documentation[2], as an archive, as an exposition of what we might have learned, or as an argument or set of intentions for engaging with exposures.Therefore we recognize the importance to delineate that we are not offering a definition of what an exposure is or what it should be (and we have come to understand that no discussion of exposures could follow from a logic of what exposures should be). In other words, we stay with both the messiness and discomfort of exposures themselves, and with what might emerge when we remember these exposures collectively. How we take up the series of events shared below is therefore more akin to how philosopher of ethical and political action, Alexis Shotwell (2016), proposes we think memory:

“we should think of memory as the relational and situated process through which we collectively determine the significance of the past for the present as a form of forward-looking responsibility”. (p.48)

The vignettes that we think with throughout this essay revisit our exposures through memory, but also do something more. Instead of propelling the facts or experiential accounts of any exposure into the present, each vignette ends with propositions that re-work these memories as proposals for the present. Through these propositions we think about the conversations, estrangement, movements, affected intentions, and risks of being exposed. We hope to put these vignettes forward as a way of thinking towards how propositions make networks and how we engage exposures in the contexts of the PNO and the ECPN as projects for forward-looking responsibility that propose other pedagogical and curricular processes – and therefore other possible futures.

In our experiences, exposures are events that complexify and broaden our imaginaries for thinking education, and necessitate that we craft different ways of enacting these imaginaries in our work with educators. For us, the destabilization of familiar educational landscapes as the root of pedagogical experience creates the tethers of a network; not in homogeneity or comfort but through webs of questions that ask how we come together as pedagogists. Because an exposure can be an encounter with estrangement or unifying in how it alters, we wonder how, in our coming together and our divergences, we enact answerability toward our pedagogical and social imaginaries.

In this essay we wonder: What is it to be exposed?

How do we Attend to What an Exposure Proposes?

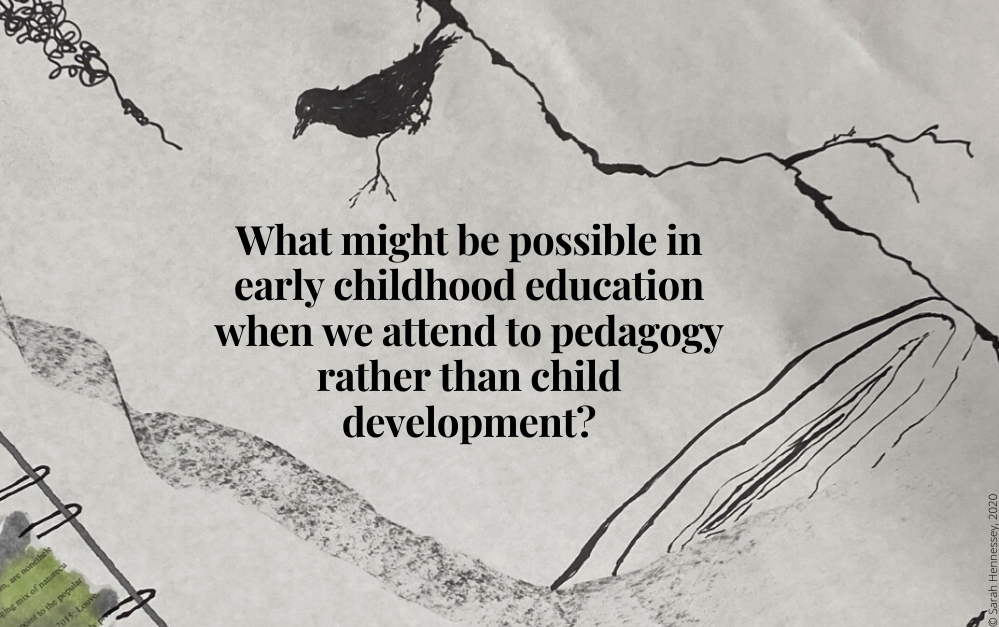

The Pedagogist Network of Ontario (formerly the Centre of Excellence for Early Years and Child Care) and the British Columbia Early Childhood Pedagogy Network have crafted various kinds of exposures over the past four years. Some have been local invitations extending the regional conversations and projects of a group of pedagogists already in close conversations. Other exposures have been large events for all pedagogists to come together across (what are often separate) networks. Since the beginning of the 2020-2021 Covid-19 pandemic, many events organized by other institutions and in other disciplines have been shared with us from our networks as invitations that might be of interest to pedagogists. When these invitations from the directors of the PNO and ECPN arrive in our inboxes, for us, they invite us to step outside early childhood education and remind us that pedagogy cannot be fostered and inspirited as an isolated discipline.

Although some events trace outwards from the conversations and projects that the pedagogist networks have already proposed, when an email invitation for one of these ‘might be of interest’ exposures arrives we find it can sometimes be hard to immediately recognize precisely how it fits within a commitment to pedagogical work. This vignette begins with this moment because we think unrecognizability conveys some of what an exposure does and can be. Unrecognizability, we feel, traces the implications of exposures for pedagogists and students of pedagogy, through the experimentation of exposures, which Cristina has come to describe as “incorporating an idea into the present without repeating the present”. Starting from a place of non-recognition allows us to begin not from what we know or might expect, but rather from the uncertain. Other events that are shared by the PNO and ECPN trace outwards from the conversations and projects that the networks have already exposed. Here we might meet familiar concepts in strange ways or we might put the questions we hold dear at risk in the face of unfamiliar explorations of what our questions and concepts might do.

As we began to revisit the series of exposures we participated in for this essay, Meagan and Lucy decided to think together about how we receive these invitations, what they ask us of us, and how they get taken up in daily life. We came to wonder, in the move from being exposed to the uncertainty of exposures, how, without careful attending to, exposures perhaps too quickly become another part of the narrative of busyness that often permeates educational contexts. Rather than first recognizing an opening of not knowing, it is sometimes the demand and too-muchness of pedagogical work and all that it is connected to that dictates how we respond to an invitation to be exposed.

In coming together again as regional coordinators, through our conversations about engaging with exposures, we explored our responsibility to ‘show up’, to engage with and be vulnerable to those we are listening to and watching speak. As pedagogists, we must do more than take quotes and ideas and find places where they fit into our work, and instead ask ourselves, what can I do with this, how can I think this concept in ways that invigorate my pedagogical work? We (Meagan and Lucy) both recalled events that we could not find time or energy to attend. We recounted being overwhelmed with the amount of online content that had flooded our inboxes since the summer of 2020, when the academic world started experimenting widely with how to continue on when the majority of us were confined to our homes. In these times, we both remembered instances we had tried to make time for the compelling events shared by the PNO and the ECPN as “might be of interest” exposures. I (Lucy) recalled unexpectedly finding time to attend an exposure at the last minute, by listening on the go with headsets, being struck both by the talk and the feeling of too-muchness that did not go away. I (Meagan) remembered deciding to go to one exposure invitation, but with earphones in while attending to piles of dishes and laundry. I was quickly reminded that this is not the disposition of a pedagogist when engaging with ideas. Within minutes, I abandoned the housework and began to actually listen to what was being offered.

As I (Lucy) have been thinking back to the various invitations to events that the PNO and ECPN have shared as part of the practice of exposures, and as I have been talking about these more with Meagan, I have been struck by Meagan’s proposal of what it means to think with a concept. In the above little vignettes on the thorny questions of pedagogical invitations entangled in multitasking and too-muchness, from similar starting points, we both engaged with exposures differently and our experiences in some ways put at odds what it means to attend to the proposal of each invitation and the unanticipated proposals of each event. This discord of experience, I want to suggest, offers an idiosyncratic proposal made from our two different ways of engaging with this event that is not instructive of how we attend or do not attend to pedagogical work. Rather it suggests the lived and messy ways that, as Meagan writes, we meet concepts and, as I would add, we come into contact with the proposal of a body of work or mode of thinking that is not recognizable in the terms of our own projects. What both of these remembrances of exposures and their invitations don’t quite reveal is how and why we have been affected by exposures, and why we might see the need to return to think with the nature of community, living together, and responding to proposals of other disciplines, projects, and places through the moment of an event, after the event has long passed.

To answer this, we turn to a particular exposure through a shift in narrative. In other words, our interest is not to now look at a moment when we engaged with an exposure with proper and full attention and the ways we were affected. Instead we want to turn to a larger question introduced to us through the poetic, historical, literary, political, and pedagogical project of Dionne Brand where the public nature of the exposure brings us into the unavoidable intimacy of the work of thinking a concept.

In December 2020, the PNO forwarded an invitation to the 2020 RWB Jackson Lecture: Dionne Brand with Rinaldo Walcott. We (Meagan and Lucy) remember this talk for the ways it spoke in a new register to the questions of what is attended to in public spaces and enactments, and how it addressed this work through problems of public memory. As we revisit this event together, our intention is not only to speak to ways of attending as ways of being affected because we think this skips over much of what Brand proposed we consider on that day. We also think it suggests the trouble of revisiting events only in terms of what they exposed us to personally. To work towards creating fissures in the dominant ways of doing education, as pedagogists and students of pedagogy, requires that we trouble some of the subjectivities that are created and (recreated) such as individualism and utility. Although often thought in terms of what is captured, known, or defined about a subject or their place in official narratives (history and state building), memory can be a work that destabilizes those dominant practices, as the quote from Alexis Shotwell in the introduction suggests and as we found and find in our conversations, as we took up memory as a social practice. For this reason we want to instead share a little more about where this conversation has taken us. We want to tell you a little about the proposals that emerged for us and a little more about the talk—about how Brand invited us to interrogate positions of innocence and what is protected through modes of forgetting. Putting these moments into conversation does not expose the ways we are affected by an event; yet, does it evoke some of the ways we continue to live with this work? On that day, in the conversation after her poem essay written in the voice of a black aesthetic, Brand (December 2020, emphasis original) as she does in this quote, spoke about the pandemic and the way she “never used [the word normal] with any confidence in the first place” (July 2020, para. 2). In this way, Brand links the problem of a protected and false status quo and the “fiction of innocence” to the delayed arrival of an urgent future (December 2020). She writes:

We are, in fact, still in that awful normal that is narrativized as minor injustices, or social ills that would get better if some of us waited, if we had the patience to bear it, if we had noticed and were grateful for the miniscule “progress” etc … Well, yes, this normal, this usual, this ease was predicated on dis-ease. The dis-ease was always presented as something to be solved in the future, but for certain exigences of budget, but for planning, but for the faults of “those” people, their lack of responsibility, but for all that, there were plans to remedy it, in some future time. We were to hold onto that hope and the suspension of disbelief it required to maintain “normal.” (July 2020, para. 2)

Threaded together with other ideas from that day that we are still digesting, (in conversation, thinking, and praxis), is our wish to attend to what too-muchness generates. How do exposures ask that we engage beyond what we are ready for? How do we meet the words and thoughts of others through lived-study? How do we search out conversations that return us in good company to what we only glimpsed in our first encounter? Moreover, what is our responsibility as attendees and listeners and pedagogists to do the searching that keeps these conversations alive in our work?

What are the Dispositions/Subjectivities for a Pedagogist to Engage in an Exposure?

In the Toronto region, I (Alicja) was thinking with a group of becoming pedagogists, and regional coordinators who were involved in a pedagogical project that has been carried into the current Pedagogist Network of Ontario. In this group, we wanted to offer a radical event that would shock us and carve out the beginnings of an unfamiliar direction for thinking about early childhood education. In our bi-weekly discussions together, we wanted to seek interdisciplinary alliances and alternatives that could move our conversations forward in ways that might disrupt the status quo. We were guided by the following commitment (at this time in a piece of writing termed manifesto):

“we understand the role of the pedagogist as emerging from a particular tradition and yet it takes shape in relation to the contexts, questions, and contingencies in which each pedagogist works. The role of the pedagogist always responds to something but it is not determined by it. The pedagogist works in collective and collaborative ways because they live pedagogy as a common project. This is why we understand the work as avowing to a collective and ethical invention. The pedagogists’ modes of thinking are interdisciplinary. Non-compliance with what is already established and prescribed is the pedagogist’s modus vivendi” (Ontario Centre of Excellence for the Early Years and Childcare, 2019)

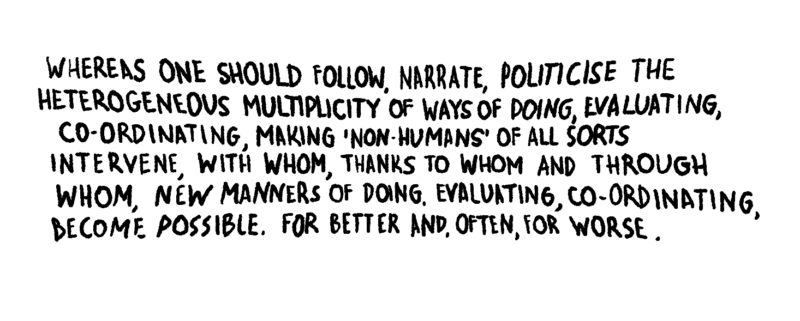

I volunteered to help with finding an exposure in the Toronto community for pedagogists. I proposed to go to MOCA (The Museum of Contemporary Art), a gallery whose existence and commitments propose a literal shaking up of Parkdale, an area in the midst of heavy gentrification. We were very intentional about becoming sensitized and responsive to the contextual place we were visiting. To orient ourselves before our visit, we (regional coordinators and pedagogists) read Ways of Following by Katve Kaisa Konturri (2018) who invited us to engage in attuning processes that follow art works beyond meaning-making, utility, or certainty. Going to MOCA, without a particular concept or closed purpose in mind – and rather with a collective commitment to move away from prescriptive practices in early childhood education (as mentioned in the manifesto), was a proposition for us to experiment with what it might look like to let go of utility, and to instead be open to the possibilities we might encounter. Because of this openness in our preparation, we focused on weaving our previous discussions about extraction and utility in early childhood education into conversation with the unknown that the exposure would present. In thinking with Konturri, we crafted the following proposition that was included in our written invitation: We are curious how we might ‘do’ ECE as an intellectually vibrant space by carefully thinking with exposures that are not only interdisciplinary in their content, but that do interdisciplinarity through their modes of expression, the ways we become implicated with their offerings, and the questions they require we cultivate together. It was important in this case, to include a link to the gallery that explored the histories of the building where it resided. We prepared to come to the gallery keeping in mind that this was space for transformation – one that previously served as an industrial factory, a radical art making space, and now a gallery that stayed with the trouble of being implicated in the region’s gentrification.

On the day of the MOCA exposure, we (a group of coordinators, pedagogists and ECE’s) met together in front of the menu list on the first floor of the gallery where the exhibits were described and had to make choices about which exhibit to see. Along with being a regional coordinator, Lisa-Marie was also working as a pedagogist with a group of educators that thought with the cutting of trees at their childcare centre). With the desire to maintain collaborative dialogues that might trouble our specific contexts, we chose to visit the exhibit The Life of a Dead Tree by Mark Dion. Despite our intentions to think about our encounters with the gallery as ones that might estrange us from our comfortable pedagogical dispositions, we were not completely prepared for the way we were unsettled by the exhibit. In order to let go of utility, we were confronted with it – and this gave us an insight into our participation in utility. Dion’s work simulated a tree lab, where hammers and pegs were used to pull out ‘invasive species’ that were later pinned in a live laboratory inside of an art gallery that Mark Dion called “The Bureau of Entomology”. We were uncomfortable as we witnessed a sterile account of ‘invasion’. While we prepared to let go of utility and to expose ourselves to openness, we witnessed a depiction of violently displayed extraction. This extraction shaped the conversation that we had as we sat together and reviewed our notes. In our conversation, we were struck by the questions that resulted from our engagement with the exhibit: Who are the invaders, and how are they extracted? This question stayed with me for quite some time, and the dead tree, its invaders and extractors, leaked into my Masters research project. Currently, I am looking back and thinking with the initial descriptions of MOCA’s relationship with gentrification, and how this question about invasion and extraction was so relevant to the space we were in.

In coming together now, to reflect on exposures and what it might mean to prepare for an exposure, we realize that we never come to exposures with a blank slate. Our intentions and orientations configure our dispositions in relation to what we encounter in the exposures, and in the case of The Life of the Dead Tree exhibit, our initial intentions ignited the uncomfortable. How do we come to an exposure with intention while maintaining and fostering a sensitization and openness to what might emerge? What/how might we need to prepare for this kind of sensitization? Thinking back to work as a pedagogist during that time, what would openness mean as a pedagogist with pedagogical intentions?

What does an Exposure set in Motion?

Picking up on Alicja’s discussion of the The Life of a Dead Tree exhibit, I (Lisa) revisited how I attended to the event both in the moment and now two years later. I recently went back to the photos on my phone to look for pictures and was surprised that I had only four. One photo was of the tree, the main attraction of the exhibit, and three were of text that described various concepts that Mark Dion was working with. My focus on the text of the exhibit did not reflect how I remembered engaging with it. The choices I made in documenting the event revealed what I now consider a wanting to be able to know and explain the exhibit in the words of the artist. Coming together now, in 2021, as a group to think about these exposures I want to attend to that momentariness of the exposure in a different way. I notice how my focus on text is a form of enacting utility and extraction instead of prioritizing openness and being in relation, being vulnerable to the exposure. As I make the choice to re-attend to the moment by revisiting my photographs, I am oriented as a pedagogist in how I not only come to exposures but how I attend to them after once I have left the moment of the event and after some time has passed. For me this draws my attention to the temporality of exposures, how might we simultaneously embrace momentariness while being open to the concepts lingering in our pedagogical work.

To be able to attend to a moment of an exposure, we must first attend the exposure, show up, and step into aspace of uncertainty and possibility. An exposure offers us a momentum and a temporality outside of the regular beat of early childhood education spaces. In the moment of an exposure there is a desire to still the momentum and capture the temporality of it by taking pictures and notes. I wonder what these methods of attending to an exposure make possible and what they make impossible for a pedagogist.

This MOCA event was my first experience of attending an exposure with the pedagogists. I was aware of my anxieties about a new experience. I had presumptions of what it meant to go to an art gallery, and how to be at an art gallery, and alongside my intentions and preparations for the exposure, I knew that experience was asking something more of me, but I wasn’t quite sure what. Perhaps the uncertainty of what it was to engage with an exposure made the momentariness of it feel precarious, like stepping into the midst of something already in motion. When I think about this movement into an exposure, I want to notice the stories and histories that are already there, both in myself, the others I am with, the exhibit itself and the place we are located. This reminds me of Tim Ingold’s (2011) proposal that the storied world is

“ a world of movement and becoming, in which anything– caught at a particular place and moment – enfolds within its constitution the history of relations that have brought it there. In such a world, we can understand the nature of things only by attending to their relations, or in other words, by telling their stories.” (p.199)

An exposure invites us into stories already in motion, already put into motion in various ways by various actors, by the artist and the art, by the reading from Konturri that orients us to the exposure and by the hopeful intentions that the exposure will do something without necessarily knowing what exactly that something is yet.

For me, reworking the memory of the exposure provides me a space to think deeply about how the stories present both on the day we attended and now, as remembering has muddied the concreteness of the event. In the newness of this experience, I leaned on ways of engaging that upheld familiar modes of utility and extraction that inhibited me from considering the other ways I might focus instead on how my stories and the stories of the exposure intertwine and diverge. As a pedagogist, I am attuned to the pedagogical questions that are set in motion through a re-attending of an exposure. How does tracing the movements and histories that bring us to an exposure disrupt utilitarian and extractative relations? How do our stories and our engagement with an exposure become part of its momentum? How do we ethically sustain this momentum by considering the stories we choose to tell, the stories we leave out and our implication in these choices?

What if we Imagine Exposures as a Refusal of Passivity, and as an Active Composing of a Different Kind of Pedagogical Thought?

Exposures are more than passive events; they require not only an openness to something new and possibly unfamiliar, but also a vigorous doing with the ideas we encounter in being exposed. Because exposures are not professional development, where we might approach an event in search of knowledge that aligns with the already known rules of our profession, we must enter into exposures with a willingness to be affected and to engage with that affect to invigorate our pedagogical work. The ways we attend to exposures is an activation of our pedagogical commitments and intentions. Cristina Delgado Vintimilla reminds us on the PNO website that

“An exposure creates a space for “being with”—being exposed to— ideas or situations that have the potential to create alterations and “redistribute the sensible” (Ranciere), as well as its ways of participating in common/shared living. Estrangement, refiguring, altering, being called by a sensing that can’t yet be made sense of are the generative instantiations that exposures offer to pedagogists, and that in turn pedagogists offer to their milieu”

In the London Region, we (Cory and Meagan) hoped to engage with local histories as a way of composing our pedagogical thinking and doing as always situated within the specificities and the histories of the places we live and work. We originally invited pedagogists to join us on a self-guided walking tour of London, ON which was curated by Hear Here London in July of 2019. Unfortunately, extreme heat advisories, risks of thunderstorms and possible tornadoes dictated that we postpone our exposure until September.

As we prepared for the walking tour, we knew that we would likely encounter narrations of the city of London that reinscribe the colonial histories of the homes and streets and old buildings we walked with. We wanted to think how we could expose and be exposed to particular narratives, but also pay careful attention to the ways in which decisions about which stories to make present and which to make absent is a non-innocent project in the country currently known as Canada. Often, our role as regional coordinators involved collaborative reading with the London pedagogists. In advance of the walking tour we offered a chapter by Fikile Nxumalo (2019) Presencing: Decolonial Attunements to Children’s Place Relations. Reading together was a practice of collective re-orienting around how and to what we pay attention to in our encounters with place. As highlighted in vignettes above, exposures are not static events, they have trajectories – befores and durings and afters – that resonate as exposures are prepared for, encountered, and taken up. We return to this point not to offer or insist on specific ways of doing exposures, but to continue to insist that these are not just ‘anything goes’ events, but ways of gathering that are specific to thinking as a pedagogist.

In our walk, we wanted to activate embodied disruption of the commonly celebrated capitalist and colonial stories in London, Ontario. We follow Nxumalo (2019) in wondering “what does it mean to tell and listen to these stories amid ongoing Indigenous dispossession and rampant capitalist colonial extraction?” (p. 162). During our walk, we asked pedagogists to think alongside us about whose and which stories were present and whose and which stories were absent. As regional coordinators, inviting the concept of present and absent stories into conversation with a curated walking tour meant refusing a passive engagement with that in which we encounter. In particular, we prioritized creating conditions within this exposure to re-compose our collective pedagogical orientations to notice and trouble the taken for granted stories that thrive in settler colonial places. In this sense, our exposure engaged with more than just the material act of walking with and listening to the curated stories of the city. It would have been easier to say this tour does not do exactly what we want it to do, so let’s find something else. Instead we said this tour might give us opportunities to activate some of the reading and discussions that we have been having regionally and centre wide. To stay with the complexities of rethinking colonial stories required resisting pre-scripted narratives – narratives of complacency embedded in quotidian encounters with the places and spaces we live – but also the curated narratives in experiences such as the walking tour. How might exposures activate a refusal of passivity, and what dispositions are required to compose and recompose pedagogical commitments in dialogue with the conditions of the 21st century?

What is the Risk of Exposure?

In the Toronto Region, we offered an exposure in which we visited Jennifer Rose Sciarrino’s exhibit From Root to Lip, which showcased “a series of sculptures referencing biotic matter—seeds, spores, cells, pollen, bacteria and yeast” (Sciarrino: From Root to Lip, 2019). Prior to our encounter with Sciarrino’s art, we read Donna Haraway’s (2015) Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin, which Sciarrino thinks with in the catalogue of her exhibit. Specifically, Sciarrino’s art laboured with Haraway’s notion of making kin by paying attention to less-than-seen biotic matter.

The invitation to participate in this specific exposure was declined by the pedagogists and only Toronto regional coordinators (Lucy, Lisa, Alicja and I, Lisa-Marie) attended. Our visit to the exhibit was brief and quiet. Each of us carefully stepped through the exhibit and spent time with each sculpture. Toward the end of our visit, we realized that the artist, Jennifer Sciarrino, had been in the room with us and we tried to eavesdrop on her conversation with another attendee. Unable to overhear or enter the conversation, we decided it was time to go. We walked down the street to a neighbourhood cafe to discuss the exhibit in relation to the reading and our ongoing pedagogical discussions in the Toronto region group. As we gathered together at the table in the cafe, we wondered why pedagogists did not attend this exposure: Did the suggested reading deter pedagogists from attending? Had pedagogists had enough of art exhibits? Was the interdisciplinary work of this exposure too foreign for pedagogists to imagine how it might extend the boundaries of their thinking in early childhood education? Or, had everyone’s minds veered away from pedagogical thinking and eased into summer vacation?

Remembering this exposure as we write this collective essay, I (Lisa -Marie) notice how the loneliness of an exposure with no response is always a risk. When our offerings are not always reciprocated by a response we are left with questions about presence and intention. While we know our collective pedagogical work is buoyed by the commitment to pick up the frayed threads of dialogical tangents and weave them through multiple conversations, there is always a risk that the animate exchanges that pedagogy requires is rejected by those we offer it to. What is it to be a network when those who compose the network decline to gather around particular propositions?

The From Root to Lip exhibit made visible the generative co-becoming of less-than-visible lifeforms and the multitude of risks of being exposed. The risks of exposure – contamination, disorientation, failure, sensitization, frustration – are unavoidable and profoundly necessary. It is through exposure that making kin is possible; making kin, being vulnerable to the contamination of the less-than-visible itself involves risk. As Haraway (2015) notes “kin is an assembling sort of word” (p. 162), and in making kin with the less-than-visible, we have no guarantees of what these assemblages might be. More precisely, the risks of making kin and exposing oneself to co-becoming is that (pedagogists’) subjectivities are unknowably fostered, made and unmade in exposures, with no guarantees for predetermined outcomes. These precarious pedagogical relationships, like the life of the less-than-visible, are contingent on caring relations, on picking up the frayed threads left open. If we consider our pedagogical relations and connections within the network as a way of becoming kin, we know we must struggle to maintain these relations because as Sciarrino’s exhibit highlights and makes visible: “Making kin is perhaps the hardest and most urgent part” (Haraway, 2015, p.165). The risks of exposure and pedagogical inquiry mimic the biotic matter that Sciarrino (2019) describes as

“growing and moving, perhaps very slowly, and we are just catching them in a single instance of an otherwise longer transformation. I see these sculptures as curious metaphors, ready to animate exchanges with each other, including those visiting. Kinship outside of genealogy would require the conditions that sustain the individual to also be hospitable to the group as a whole” (para. 17).

So, perhaps the risk of exposure is less about loneliness and more about the uncertainty of being exposed to and exposing less-than-visible worlds. How do we attend to risky exposures – and what do we hope our exposures risk? How are our worlds always already populated by relationships that are woven together but also put at risk by collective vulnerability?

Recollecting Exposures, Together, Again

Our intention in this collection of vignettes is to revisit our memories of particular exposures in unfamiliar ways. This way of tracing, we offer, corresponds to the modes of experimenting we try to attend to with exposures. When we began going back to the exposures discussed in this essay and the fragments of documentation we had kept, we did not quite know how to describe the complexity of our various engagements and recollections of these exposures. However, we knew that a recognizable historical account of these events might pursue something quite different than the complexities of attending to memory as relational and situated processes (Shotwell, 2016). When we started writing this essay we did not fully realize the scope of the exposures within the The Pedagogist Network of Ontario and the British Columbia Early Childhood Pedagogy Network. As we recollected these exposures in the writing and conversations of this essay, we realized the significance of the questions we were grappling with in both our regional and large group exposures. We noticed the ways we relate to pedagogical work were altered through our engagement with the exposures. It is partly this realization that has led us to experiment in this essay with tracing how we carry the happenings of these exposures with us in our work and thinking now. The concepts explored in the vignettes above – conversations, estrangements, movements, affected intentions, and risks – were put in motion through our fragmented memories of the exposures, which revealed for us the ways that concepts and proposals made from memory do something new with the present. For us exposures have created proposals to think with others as a way of forward-looking responsibility that enable us to think beyond the boundaries of the familiar worlds of our classrooms, collegial networks, and the bannisters that support our everyday practices in education. In recollecting exposures, together again and again, we wonder how the practice of fragmented memory work continues to move our pedagogical work. As we come to what might be an ending in this essay – we offer in this conclusion as a form of beginning again – we want to return to our questions from the beginning of this essay: namely, what is it to be exposed? This is not a question that leads to any kind of conclusion, but in our vignettes instead we think about the dispositions we embodied to be exposed. How do we remain in the discomfort of conversations, estrangements, movements, affected intentions, and risks? What does this discomfort make possible towards pedagogical work?

Footnotes

[1]

We are grateful for Cristina for making herself available to us so we could learn more about the historical background of exposures as we were writing this essay

[2]

We agree that documentation also does something more than revisit through memory. However, we do not see this essay as a work of documentation because for us documentation works towards a particular pedagogical project. Here, we are interested in how these exposures are part of this pedagogical work, but we don’t think we take up the exposures here in a way that furthers the pedagogical work of the network in a form akin to documentation.

References-MM-LA-CJ

Introduction to the authors and our work with exposures:

Lisa and Alicja first experienced exposures as graduate students through their work as assistant regional coordinators and research assistants with the Provincial Centre of Excellence for EarlyYears and Childcare. Now as PhD students and community pedagogists with the Pedagogist Network of Ontario, Alicja and Lisa continue to engage with exposures and weave them into their work. Alicja is also engaged in thinking with exposures through her ongoing work as a pedagogical coordinator with an itinerant school as part of a larger research project for pandemic times in Cuenca, Ecuador. Meagan is a PhD candidate at Western University in the Faculty of Education. Alongside Cory, Meagan was a regional coordinator for the London Region and continues to work with pedagogists in British Columbia and in post secondary education. Lucy was introduced to the practice of exposures when working as a regional coordinator in Toronto for the Provincial Centre of Excellence for EarlyYears and Childcare and. Lucy continues to attend to and explore the invitations extended as part of the practice of exposures as a participant in the post-secondary network of the Pedagogist Network of Ontario. Together with Lucy, Lisa-Marie was a regional coordinator for Toronto Region. Lisa-Marie is a PhD candidate at Western University in the Faculty of Education and continues to participate in the pedagogist network of Ontario. Cory is a PhD candidate at Western University in the Faculty of Education and was a regional coordinator alongside Meagan for the London Region.